Plastic Surgery: The Surgical Specialty of World War One

11th November 2018

The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) and the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) have shared a collection of photos showing the early development of plastic surgery during World War One (WW1), to commemorate a century since the end of war.

BAPRAS holds an incredible collection that documents the history of plastic surgery in the United Kingdom from WW1 to the modern age. It preserves surgical instruments, images and papers relating to the growth of this surgical specialty in the 20th century.

The Royal College of Surgeons will host a free drop-in event from 2-5pm on Saturday 17 November 2018 to give the public the chance to see some of the objects and images from the BAPRAS archives that record the pioneering work carried out in the United Kingdom during and after WW1. Visitors will be able to chat to archivists and discover the remarkable stories of those that survived WW1.

Commenting on the collection of photos, David Ward, President of BAPRAS, said:

“Harold Gillies created and led the teams that reconstructed these badly injured soldiers, developing new techniques that have stood the test of time. These have formed the basis of the plastic surgery skills used today, and indeed still have their place in our armamentarium.

“We have much to be thankful for to Sir Harold and his colleagues.”

Words by Mr Roger Green, Retired Plastic Surgeon and BAPRAS Honorary Archivist.

All wars create important advances in the management of trauma, but WW1 has the particular distinction of having created a completely new surgical specialty.

Plastic surgery is the surgery of reconstruction; its goal is to regain appropriate function as well as achieving a satisfactory appearance.

Courtesy of BAPRAS.

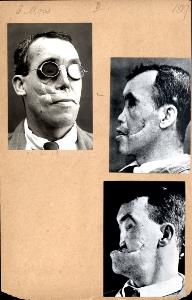

Cheek injury.

WW1 was a desperate war with the needless slaughter of millions. But there were also ‘les mutillés’, the enormous numbers of war-wounded. Amongst the melee of the forward clearing stations, came devastating facial injuries caused not only from machine gun bullets but also from shrapnel, huge shards of metal from exploding shell cases, which ripped faces apart.

Credit: Courtesy of the RCS.

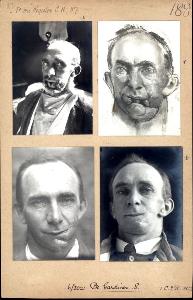

Patient ‘Gardiner’ before and after reconstructive surgery, including a sketch by surgeon Henry Tonks.

In a moment it created a person who could not speak, could not eat, and could not easily breathe. They were left significantly disfigured, and struggling with the awful and inevitable psychological burdens from which every soldier suffered.

Injuries of this magnitude had not been experienced before. In prior wars soldiers with such injuries would not have survived, so there was no guidance for surgeons in the management of these patients.

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

Sir Harold Delf Gilles.

Harold Gillies, (later Sir Harold) was a young surgeon, sent to Belgium in 1915, who became intrigued with these injuries and busied himself trying to solve the conundrum. His success and his tenacity led to his being sent back to Britain with instructions to set up a hospital specifically for the treatment of facial injuries.

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

A ward at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup.

Gillies was firstly at the Cambridge Hospital Aldershot, where he initially admitted 30 patients, but the hospital soon became unable to manage the vast numbers of patients returning from the front. As a result he subsequently supervised the construction of Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup, which opened in 1917, initially with 320 beds but which increased to some 2000 by the end of the war.

Credit: Unknown.

Sir William Kelsey-Fry.

Gillies was joined by William Kelsey-Fry, who was qualified in both Medicine and Dentistry, and together they developed a multidisciplinary team, which could jointly treat both bony and soft tissue elements to progress the development of this new specialty.

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

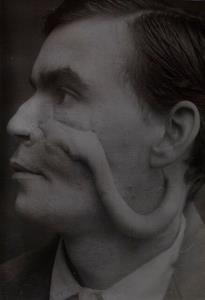

Forehead flap to cover nasal injury.

Gillies needed to find new tissue to replace the parts of the face that had been shot away. He developed the use of flaps of skin which maintained their blood supply, however these were not always able to reconstruct either the loss of a very large area, or to stretch far enough to cover the damaged area.

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

A tube of skin taken from chest to cover a large cheek defect.

Gillies devised new methods for moving tissue in stages using a tubed flap, which, by reducing infection that had so badly hampered progress in the past, enabled large areas of skin to now be moved from a distant part of the body.

Credit: Courtesy of the RCS.

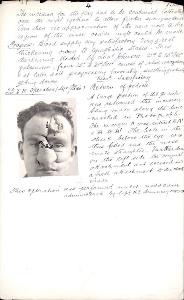

Detailed plan of proposed surgery drawn on photograph

By close inspection and observation, Gillies would assess the amount and type of tissue lost and what would be required for repair. He then designed and recorded a plan of management for each individual patient.

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

A group of patients at Sidcup. A journalist wrote that he was impressed by the cheerfulness of everyone.

Whilst plastic surgery successfully repaired may thousands of faces there would always be scars physical and mental. But could anything really prepare a soldier for future life? Could the ‘hero’ of the war walk down the street without being stared at? Would he be accepted back into the family, or by the girlfriend he left behind?

Credit: Courtesy of BAPRAS.

Sidcup patients Football team 1921-1922.

Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup organised occupational therapy through carpentry shops, gardening, and business studies. Sports such as tennis, cricket were also encouraged, and they had a very successful football team.

Credit: Courtesy of the RCS.

Patient ‘Moss’ before and after undergoing reconstructive surgery.

The work continued after the war for many years. Gillies continued to develop his ideas, writing the first textbook on the subject in 1920 to record his approach and methods devised at Sidcup. He subsequently directed the management of casualties in WW2, and was the founder of the British Association of Plastic Surgery (now BAPRAS) in 1946.

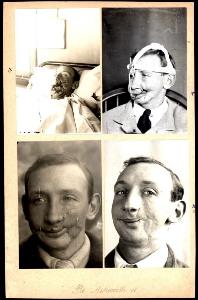

Credit: Courtesy of the RCS.

Patient ‘Ashworth’ before, during and after reconstructive surgery.

In a moment it created a person who could not speak, could not eat, and could not easily breathe. They were left significantly disfigured, and struggling with the awful and inevitable psychological burdens from which every soldier suffered.

Injuries of this magnitude had not been experienced before. In prior wars soldiers with such injuries would not have survived, so there was no guidance for surgeons in the management of these patients.

It has been said by a soldier that you are unable to have that sort of experience without it directing the rest of your life.

*******************

Commenting on the collection and role of plastic surgery, Mr Tim Goodacre, Plastic Surgeon and Royal College of Surgeons Council Member, said:

“Being able to see these pictures that give such a vivid and poignant perspective of the horrific injuries that so many soldiers endured during the Great War, especially with the extraordinarily bizarre new ways of reconstructing their features, gives us now a real sense of the privilege that advances in plastic surgery have made over the past century. These early pioneers of plastic surgery devoted their work to helping the afflicted soldiers to be able to face society again and go on to live as normal lives as possible.

“These days, so many people think that plastic surgery is only for frivolous cosmetic changes by those who have little medical need – a view that is seen all the time in glossy magazines and advertising everywhere. The reality of plastic surgery is that it is a huge area of surgery that is used across all ages to treat a great number of conditions in people with disfiguring wounds, injuries, cancers, and birth deformities, to restore their ability to face the world.

“So many of the incredible advances in rebuilding bodies began with the pioneering surgery of the WW1 surgeons and teams – and continue to do so within the NHS alongside great research from the armed forces medical services today.”

Notes to editors:

- High resolution photos and permission forms available on request.

- Photos and captions curated by Mr Roger Green, Retired Plastic Surgeon and Honorary Archivist, BAPRAS, and Ruth Neave, Collections Officer (Plastic Surgery), BAPRAS.

- Editors are kindly asked to ensure that all images are correctly credited.

- A free drop-in event, ‘Facing the Past: WWI Plastic Surgery, exploring the BAPRAS archives’, will take place at the Royal College of Surgeons on Saturday 17th November 2018. Further information is available here: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news-and-events/events/calendar/explore-archives-bapras-171118/

- The Royal College of Surgeons Museums hold a large collection of Tonks’ watercolour pastels of reconstructive surgical procedures which can be viewed on our online catalogue Surgicat http://surgicat.rcseng.ac.uk/

- The British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons is the voice of plastic surgery in the UK, advancing education in all aspects of the specialty and promoting understanding of contemporary practice.

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England is a professional membership organisation and registered charity, which exists to advance surgical standards and improve patient care.

- For more information, please contact the RCS Press Office Telephone: 020 7869 6052/6047; email: pressoffice@rcseng.ac.uk; or for out-of-hours media enquiries: 07966 486832.

Back to list page